THE INCOMPARABLE “El Juli” !

I came late to bullfighting and left early, but not, as I shall explain, because it disgusted me. My arrival was a matter of propinquity. I happened to be living in La Macarena, the downtown neighborhood in Bogotá where the Santamaría plaza de toros (cum open-air theater) is situated. Even for my neighbors who were indifferent or busy with other pursuits, it was impossible to remain unmoved by the anticipatory excitement of the crowds who thronged the surrounding streets, among whom one spotted celebrities, politicians and other members of the Colombian elite whose attendance was de rigueur. The ticket-holders (many men in berets and red sweaters with consorts in Cordovan hats) filled every parking spot (or double-parked), topped up their wine skins at the corner store everyone in the district went to and fought their way to the entrance through scalpers, pickpockets, picador´s horses and hawkers of snacks, drinks and foam-rubber bum seats, then, passing barricades, waited on long lines to go in.

Nor, when it started, ignore the bugles, band and waves of olés, heard in my apartment three blocks away. How I finally took the plunge, I cannot remember, but I think it had something to do with my fascination with all the quirks, customs and folkways of my adopted country. The first time, I was bowled over, less by the corrida as such but the sheer colorfulness of it all. The opening procession: the mounted bailiffs, followed by the toreros and their squadrons, followed by the pike men on horses armored like Hannibal´s elephants; the music of the paso dobles, the salute to the president, doffing of caps, the key which opens the spectacle and the stands like a pointillist tapestry broken by the solid bands of color of the uniforms of the peñas (clubs of aficionados).

And that´s only the start, but sufficient to convey the spirit of the fiesta brava, in which courage is inextricably linked with dignity and composure. A bull fight it isn´t but a ballet between man and beast, a passion, a romance, which necessarily ends in death but doesn´t glorify violence. Just the opposite: it is a battle of wits, grace, athleticism and, especially, empathy: the matador at one with the bull.

This, the discipline of the matador, his respect rather than hatred of his opponent, to the point where he says that the bull is his best friend, marks a strong contrast with the sports I grew up with (if that is the appropriate term for the spectacle). If you want brutality, try (American) football. So many complaints about bullfighting, when the NFL leaves half of its pros with permanent brain damage. So much about killing an animal, when most of us devour the meat of bovines tortured in slaughterhouses (and traditionally at least, that of the toro de casta was distributed to the poor). If you want the benumbing of the Roman circenses, try baseball, noble to begin with, but now plagued by sabermetrics, giant t.v. screens that many watch instead of the field, the shooting of free tee-shirts, amplified music and other idiocies. However, I´ll grant one advantage to its commercialization. For one who is interested in the technicalities, watching baseball (at home) on the telly (a major source of MLB revenues) is much more informative than live and direct (incidentally, not so in televised golf, where the instantaneous stats on velocity, loft and so forth are a distraction). Yet, in a way, it only heightens the contrast between the bullfight and sports. The corrida has a spirit, impossible to define, which they lack. Proof of it is the lifelessness of the bullfights televised in Spain.

As a game, soccer is decent, but its off-field xenophobia and capitalist exploitation spill onto the pitch. Golf? Perhaps to an extent (its silent absorption in the moment) but, as with baseball, it´s less a question of the on-course spectators actually watching nowadays than, four deep behind the ropes, taking photos of it on their cell phones, a presage of what might happen if the Saudi-backed LIV circuit buys it all up and turns it into a mere spectacle with amplified mood music debased into a team sport. That´s apart from the demented, high-tech improvement of clubs and ball, which has led to an arms race between courses which are too short for drives which are too long. As a glance at any online golf magazine will show, it is driven by a whole industry, whose aim is fool the mediocre weekend golfer into buying pricey equipment instead of blaming his plus-100 on himself, especially the retiree kind I used to watch in South Florida, for whom the sport was only a pretext for kibbutzing, 19-hole drinks and boasting about how much money they spent on the stuff. About the only sport I know of which retains some of its original purity may be tennis, with its gentlemanly etiquette, restrained spectators and simple equipage.

With the corrida, on the other hand, there are absolutely no technological or advertising distractions. It is like going back in a time machine to 17th or 18th century Spain, an age, which, for all its nastiness, had a courtly grace and splendid pageantry.

An ironic admission, perhaps, from a nice Jewish boy from the Bronx. How to explain the impact of the corrida on him: exoticism, romanticism, defiance of parents and their ethical culture milieu? All I can say is that, at first sight, he was hooked: it was all so novel and maybe for that reason alone, so thrilling as well. As for any mistakes which follow, what can a kid from the Bronx know about bullfighting? Still, it depends. Sidney Frumkin, a lad from an Orthodox Jewish family in Brooklyn, turned into Sidney Franklin, the first American to become a successful matador in Spain (who also lent his expertise to the gringo arch-aficionado Hemingway).

Since the ground has been so thoroughly covered by other writers, I´ll skip over a detailed description of the corrida and limit myself, instead, to a superficial, impressionistic account of some of the high points which have lodged in my fallible memory. The solid wooden wall of the stockade opens and the bull rushes forth: a little confused, but belligerent as he charges, this way or that, into any real or imaginary obstacle, like the burladero (shelter) or inner fence of the ring. For those few in the know, virtually everything a skilled torero needs to know about it is revealed in a matter of seconds: its pluck, gait, speed and, among other traits, tendency to swerve to one side or the other, which is further assessed when the torero, behind the burladero waits for the bull to go by and waves his cape back and forth to see how it reacts. It is also an opportunity for the subalternos to do some fancy cape work, though generally at a much safer distance from the horns than the torero.

Then the blood-stirring bugle call, the very insignia of the spectacle, announces the first stage or tercio (third), which, like the following two, adheres to the strict time limit the bugle marks: going beyond it will disgrace the torero. This third has two parts, in turn. The first, as I understand it, is essentially a warm-up: a test of the bull´s reflexes The second is the turn of the pike men, who, usually fat and middle-aged, don´t seem to have any athletic skills but compensate for that with horsemanship, the key to which is aplomb, both in the usual sense of composure and the root one (from lead) of heaviness, the weight which keeps the rider firm in the saddle and in control of his mount, as it faces the assault of an angry, horned, 500-kilo monster, which (short of a cavalry charge) is the most perilous situation any rider can face.

The anti-taurinos often adduce the confrontation in this half (suerte), the suerte de lances, as proof of the cruelty of the corrida. Bloody and violent, it is, but not sadistic nor aimless either. The idea is to weaken the bull so that it will bend its head and horns, from then on, when facing the torero, but, n.b., only a little. With the bugle again, the second starts, the tercio de las banderillas, the little darts (with a kind of feathery adornment of colorful ribbons on top) that the torero harpoons into the bull´s loins. For me, (when it is done well), this is an unparalleled feat of timing, agility and split-second judgment, which (in my cloudy memory) requires the torero and/or his subalternos to approach the bull at an angle and, at the very last moment, leap, pierce and turn away, a very tricky maneuver because as the man runs, the bull gallops.

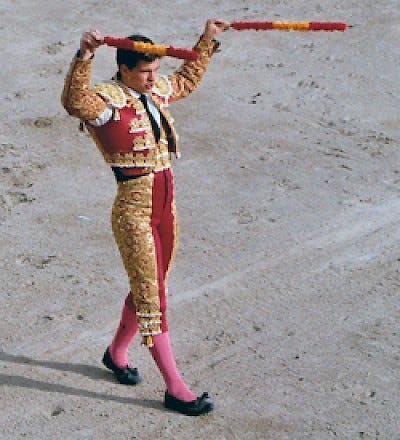

Perhaps my most memorable time at the Santamaría was watching “El Juli” sticking the pins in, the boyish-looking idol of Bogotá (and still youthful about 20 years on). As this part is often left to the subalterns, the crowd had to plead with him to perform and his artistry brought everyone there to their feet. Once again (and remembering that the beast has a very thick hide), the point is not to torture but vivify it.

Another bugle call and onto the climax, the not quite aptly named Tercio de Muerte, which, as I at least have witnessed it, refers more to a matter of fact than the Hemingwayesque bullshit about eroticism of violent death. Now the matador is (aptly) on his own for the first time. How the hell he manages the muleta, a cape which is smaller than the one (capote) he has used before, is a mystery to me and, I´d guess, everyone else as well, in that it is an awkward-looking affair, stretched on a wooden dowel and, in right-hand passes, the sword as well. Only recently did I realize (from a YouTube documentary on the great Colombian torero, César Rincón) that the capote is just as difficult to wield, due to its weight, which you or I couldn´t hold up for than a minute, and more so when it is saturated by rain.

This is the opportunity for the bullfighter to show his stuff, baiting the bull to charge (with a provocative gesture or shout of “hey, toro, toro”), and then, with a turn or swirl or lift or wrap-around of the little cape (among other complicated passes or maneuvers), bewitches the bull into dancing with him, for when done right, that´s what it is, a sublime ballet, all useless, however, if he doesn´t get close to its horns (the mediocre torero will cheat).

Since tickets are pricey, I would buy one for a seat in the two or three rows at the very top. (Ironically, since it is the only roofed part of the plaza, I was better off than the toffs when it rained). It was a great vantage point for appreciating the choreography, as it were, of the faena, which, at this point, revolves around the passes. However, it was here that I began to part company with the dyed-in-the-wool Anglophone fanatics like Hemingway, Barnaby Conrad and Kenneth Tynan. With the book of the first as primer, I began to study that art, adding a number of manuals with photos or drawings. But it remained a mystery to me, one of several reasons why I stopped going to the corridas (more below).

Nor could any mere guide, novel or poem convey the up-close, scrotum-tightening reality of it for the torero, which would come towards the end of the afternoon, when the ushers were relaxed about gate-crashers and I would sneak my way (standing) into the front rows: the dust raised, the pounding of hooves, the rush of what looked to me like a blurry, brown, low-slung armored tank (with the same expressionless features).

Even so, of the overall arte de Cúchares (a famous 19th century torero), I did get brief glimpses. Looking back now, I can hardly distinguish one artist or his performance from another, but I did witness what even the experts agree was one of the greatest suertes de capotes in the Bogotá plaza, when the abovementioned César Rincón (who is to it what Babe Ruth was to Yankee Stadium) mesmerized the bull to the point of a slow-motion equivalent of a kind of joint pirouette where the four-footed bull seemed to stand on one toe as it whirled round and round the man (practically touching him): two ears, though it deserved the tail as well!

Onto the end. Curiously, there is a resemblance between golf, the most-injury free game, and bullfighting (where getting gored is a hazard which few, if any, professionals, are free of). Just as the miss of a one-foot gimme putt will undo a 320 yard drive, the most magnificent cape work will ruin a faena if the kill isn´t swift and clean: hence, the torero is or should be the matador as well. Again, (after lining up the bull just right), how the hell does a mere human, armed only with a slender sword (steel, not mock, now) fearlessly let the monster approach, leap over its horns at the very last moment (not sideways, which is cheating) and thrust it into an aperture, the size of a big coin, to sever its aorta (so that it instantly dies) and . . .instantaneously turn, to come out unscathed!

The proof that it ain´t easy is that it is often botched. To the boos of the crowd, the torero may try again and if he still fails, is humiliated when another torero resorts to dagger thrusts in its neck. Bloody and savage, to be sure, but the question of cruelty has to be judged in terms of the suffering of the bull. This is necessarily subjective. From what I´ve seen, the bull dies in the heat of battle, fury obliterating pain. And, however regrettable, finishing it off with a dagger is meant to stop it from suffering more.

For all its archaic protocol, the faena isn´t free of humor. For example, when the torero begins to use the muleta, he will literally throw his cap (montera) into the ring and if it lands upside down, it is a bad omen, symbolizing a cup full of blood, whereupon he will simply replace it, top up, and share a laugh with the public. This also happens (though in a more quarrelsome way), when, the faena now ended, the president judges the performance of the bullfighter and awards him one or two tails (plus an ear if it is exceptional) or no tails at all. It isn´t like instantly deciding on an offside in soccer. As a privilege of rank, the president takes his time, baiting the expectant crowd, who will whistle for a decision and whistle their disapproval more loudly if he doesn´t give what they think is the award the bullfighter deserves. A little sadistic fun, you might call it.

Finally, the mules drag the carcass way, and with the sixth dead bull, it´s all over. The spectators fight their way through the narrow exits, once to the point (as I saw myself) that César Rincon, by then a civilian, needed a phalanx of ten to protect himself from the well-wishers who were crushing him; the spectators clog the streets of the Macarena again, those with cars tip the street people who looked after them and those who don´t head home (but have the wherewithal) go to an after-party at an upscale restaurant.

There are several more arguments in favor of bullfighting which its opponents are unaware of. One is that, in a way, it is fairer to the bull than the man, who has a chance to kill its adversary and, though killed itself in the end, at least enjoys the satisfaction of revenge. If the bull is a coward, on the other hand, like Ferdinand, the hero of one of my favorite illustrated books as child, he is shamed and dismissed but (traditionally) any torero who likewise fled the fight in terror in Spain would be sent to jail (though only for a few days). Contrariwise, the bull which displays an exceptional skill and valor receives an indulto (pardon), though it is less out of generosity than the opportunity for it to breed more of the same.

Another is that the toro de casta is not just an embodiment of brute (i.e. unthinking) force. In fact, he is such an intelligent animal that by the end of the twenty minutes or so of a faena, he has learnt all he needs to know about the tricks and tactics of the torero but it is too late, by then, for him to apply it. For that reason, giving a pardoned or disabled bull a second chance is strictly forbidden. Nowadays, that is. In the past, shoddy entrepreneurs would recycle the bull at a secondary plaza in Spain and many a torero was killed as a result.

To return to my renunciation of bullfighting. It was not only the passes which mystified me, but the reason why one matador I thought was pretty good angered the crowd, while another who was so-so won their applause. Plus, minor details, like why the spectators whistled during the tercio de varas (stage of pikes): were they booing the man, the horse, the bull or the attendant (safety-net) toreros? It was frustrating to be so fascinated yet so ignorant and I gradually realized something I should have known all along, namely, that unless you have grown up with a sport (again, if that´s the right word here), it´s impossible to master its fine points. My childhood ones were the balls of base, basket and (American) foot (surely a misnomer for soccer fans) and to a lesser degree (as more of a participant than spectator) tennis and golf. As for the others, rugby is beyond me and cricket even worse (which I would perforce watch for a while when I lived in England). I would make an exception for soccer, which is elementary enough for me to appreciate its athleticism without bothering about its intricacies and in any case limited to the finals of the World Cup, and then mostly as a sociological phenomenon. But bullfighting? No way would I master it, hence I was humiliated, but you might also say that giving up was a matter of respect for its nobility.

The lack of it on the part of sections of the public was another reason. For the elite, a small minority, it was an opportunity to shine and assert their tribal identity but they nevertheless behaved well. The real experts were few: the journalists, breeders, impresarios, organizers, assorted hangers-on and wealthy patrons of the art (they who would host lavish parties or country weekends for the stars of the corrida. Before the start, they tended to gather at the puerta de cuadrillas, the gate through the toreros and their crews enter the ring. But they were very clannish and, like any outsider, I both envied and resented them. They were also among those, sitting in the front row, whom a torero might dedicate the faena to by presenting them with his cape which was then draped on the shelf in front of their seat. However, since I was so far away from them, they were no bother.

The pests were a good number of the average Joes around me, for whom a bullfight was a kind of rumba where you get drunk on rioja wine, cry olé in the wrong places and shout unwarranted insults at the matadors in the belief that just because they occasionally visited their family´s farm and herded a few cows, they knew more about the corrida than anyone else. They say it is different in Spain, but for someone whose only chance to (seriously) study the thing was Bogotá, it was disheartening.

All of the above being so, my readers will wonder why I have blathered about it for so long. Truth to tell, I hadn´t given it more than odd thought for two or so decades when I accidentally came across the prompt for and moral of the whole story. Oddly enough, it arrived from what you might call the opposite pole of reality: The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell´s account of the grim lives of coal miners in the Depression-ridden England of the 1930´s.

But the book is not limited to a very meticulous study of their working conditions, standard of living, customs, mentality and so forth (supplemented by the technical and economic aspects of the industry). It is a perceptive study of English attitudes in general at that time, with a special focus on the strengths and weaknesses of the putative defenders of the miners, the militant and not so militant members of the left, among them the well-meaning socialists who believed that the solution to the problem of the miners and the poor in general was a kind of benevolent, welfare state dictatorship: the clearance of the slums in the city center, council house estates on the outskirts, restrictions on the uses and upkeep of the same, a limited number of stores and pubs, etc, down to compulsory delousing at times.

It is worth quoting some excerpts:

“[The beneficiaries] are glad to get out of the stink of the slum, they know it is better for their children to have space to play about in but they don´t really feel at home . . It is not that slum-dwellers want dirt and congestion for their own sake, but they don´t really feel at home . . .there is an uncomfortable, almost prison-like atmosphere, and the people who live there are perfectly well aware of it . . .”

And, especially, the quid of his argument: “I sometimes think that the price of liberty is not so much eternal vigilance as eternal dirt”.

My purpose is to extrapolate that to bullfighting, and rephrase it, more or less as follows: “the price of liberty is not so much eternal safety and material well-being as the acceptance that to be lived to the full, life must acknowledge the eternal presence of danger, risk, disorder, the unexpected and so forth”.

As it happened, I´d written along much the same lines, some years before, in my still unpublished novel on the Colombian narco-war, as experienced by me, from a safe distance, in a middle-class district in Bogotá, not far, however, from the more sordid and sometimes dangerous sector of downtown:

“It was a perpetual freak show. All the problems that tax the energies of “reformers” spilled out onto the streets, in the absence of the hiding places which had been created for them in the developed world (ghettos, prisons, hospitals, asylums, old age homes, even compulsory schools). The result was an open-air exhibition of all the deviations from the supposed norm (promoted here, as everywhere) of the smiling, two-kid, car-owning family. While its run of the mill turns might depress or annoy, when not taken for granted (bums, beggars, whores, addicts), others were riveting: a bag lady with a bodyguard of ten dogs, an ex-pug who cut silhouette portraits with a scissors, an elephantiasis-man baring his bloated leg. Now that the relativism of my values had brought me so close, however, it would have been stupid to let the implications of all that stop me. I had to regard it as a necessary corrective to the institutional approach of the First World, which, however ameliorating, disguised anything disagreeable as such, in the name of a bogus hygiene that was really meant to control everyone”.

To put it another way, to really flourish, the human spirit needs a measure of anarchy and as a defiance of the conventional rules, that is exactly what bullfighting provides us with: a temporary release (symbolic rather than actual for a spectator) from the imperative to study hard, find a good job, become a “success”, save money, be a good family man and so forth, so that at the end of it, you retire with a hefty pension and die of the boredom you only then realize was the condition of all that went before.

I do not defend risk or danger for its own sake, that is, as an adrenaline-high which people like free solo climbers are addicted to, though I do admire them. Instead, I am referring to courage, courage in the more positive sense that, without it, none of us would never have reached the healthy, comfortable and, to a certain extent, civilized lifestyle we enjoy today (referring to my readers at least). In my view, bullfighting is ultimately a tribute to the founders: those proto-humans who, thousands and thousands of years ago, warded off predatory animals with a burnt and sharpened stick, protected their families from marauders outside the cave and wandered over endless deserts, jungles and ice fields to clear a wilderness, build a suitable home, cultivate or hunt and (though it wasn’t intentional) propagate the sheltered and increasingly etiolated species we are today.

Were talents as various as Goya and Picasso, or Lorca and Hemingway, only sadistic reactionaries or benighted romantics. No! They appreciated and conveyed the value of the life force which uniquely runs through the fiesta brava.

Note: In Colombia, that splendid artistic tradition is being carried on by Antonio Caballero, the bullfighting columnist for its major daily newspaper: commentaries which, while brief, are literary gems.